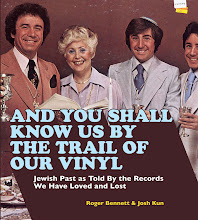

It took some pleading with his manager and a few weeks of hilarious cell phone tag, but we finally made it to a Korean bakery in a strip mall in the heart of L.A.'s Koreatown to sit face to face with the great Johnny Yune. Pop culture junkies will recognize Yune from his 1982 "Asianploitation" martial arts satire They Call Me Bruce:

which helped get Yune spots as a judge on the 1984 Miss Universe pageant, as a guest on The Love Boat, and as host of his own variety show:

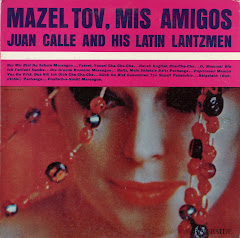

But for us, he is forever the "Jon Yune" of Ose Shalom, his 1975 album of Jewish and Israeli songs, sung entirely in Hebrew and Yiddish. The cover of the album finds Yune posing in front of the United Nations, which we always thought was an odd choice for such a culturally specific record, but Yune had his reasons. "I could sing in 16 different languages and I wanted to have a symbol of the whole world there," he told us. "But especially the American flag, because only in this country could a Korean guy sing Hebrew and Yiddish songs." Yune left Korea for New York in 1962 and he became a regular in the audience at Cafe Exodus, one of a few Jewish-themed nightclubs in 1960s Manhattan. After a fluke invitation to get on stage to sing a number (he did it in Italian), Yune was invited back but he had to sing in Yiddish or Hebrew. He started listening to albums by Israeli chanteuse Yaffa Yarkoni and had "My Yiddishe Momme" down cold, and was soon making 85 bucks a week and all the falafel and pita he could eat at Exodus, El Avram, Cafe Sabra, and Cafe Tel Aviv.

"Before I knew it I knew so many Hebrew and Yiddish songs and I had fallen in love with the music," he said. "Almost every Jewish song is in a minor key. There is a sadness to life. Koreans went through almost the same situation with 60 years under Japanese occupation and they treated Korean people like animals, just like the Jewish people were treated so badly. So I could feel that. Im not Jewish but I feel the same oppressions from when I was a kid under occupation." Which is why to this day, Yune still closes his Vegas act with his rousing version of "Exodus," putting his own spin on "walking without fear" across a "land that is mine."

"Before I knew it I knew so many Hebrew and Yiddish songs and I had fallen in love with the music," he said. "Almost every Jewish song is in a minor key. There is a sadness to life. Koreans went through almost the same situation with 60 years under Japanese occupation and they treated Korean people like animals, just like the Jewish people were treated so badly. So I could feel that. Im not Jewish but I feel the same oppressions from when I was a kid under occupation." Which is why to this day, Yune still closes his Vegas act with his rousing version of "Exodus," putting his own spin on "walking without fear" across a "land that is mine."

"Before I knew it I knew so many Hebrew and Yiddish songs and I had fallen in love with the music," he said. "Almost every Jewish song is in a minor key. There is a sadness to life. Koreans went through almost the same situation with 60 years under Japanese occupation and they treated Korean people like animals, just like the Jewish people were treated so badly. So I could feel that. Im not Jewish but I feel the same oppressions from when I was a kid under occupation." Which is why to this day, Yune still closes his Vegas act with his rousing version of "Exodus," putting his own spin on "walking without fear" across a "land that is mine."

"Before I knew it I knew so many Hebrew and Yiddish songs and I had fallen in love with the music," he said. "Almost every Jewish song is in a minor key. There is a sadness to life. Koreans went through almost the same situation with 60 years under Japanese occupation and they treated Korean people like animals, just like the Jewish people were treated so badly. So I could feel that. Im not Jewish but I feel the same oppressions from when I was a kid under occupation." Which is why to this day, Yune still closes his Vegas act with his rousing version of "Exodus," putting his own spin on "walking without fear" across a "land that is mine." There is nothing novelty about the music on Ose Shalom-- it is a deeply earnest and often intense album, so much so that when we played it for legendary TV producer Norman Lear (who writes about it in our book), Lear got emotional, steamrolled by memories of his own Yiddish-speaking family. Yune is mostly known as a comic and Ose Shalom was his first and last recording, but when he talks about it, it's clear that it still ranks as the most profound moment of his career.

For us, it's a major testament to the power of cross-cultural exchange and an amazing window into a 1960s Jewish music scene where all outsiders could find their voice. 'I dont converse fluent Yiddish, a bissel, you know, a little bit," Yune said before we left. "When I speak in Yiddish they say I used to have a Gilitzyaner accent! Some people tell me I speak with a Litvak accent! My Hebrew pronunciation is pretty good actually. I still enjoy speaking in Yiddish when I can and when I perform for Jewish audiences I always sing Yerushalayim Shel Zahav, Jerusalem of Gold. When I was in Israel, I sang that sang overlooking the Gethsemane garden and Golden Dome of Jerusalem. I had tears in my eyes."

+img037+copy.jpg)