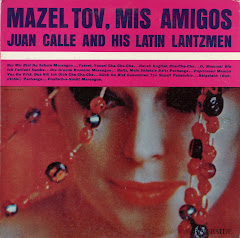

Irving Fields is a favorite of ours We used to play the Star Liner cruises with him and would never miss a night of his piano melodies at the Waldorf. We still try to catch him at Nino’s in Mahattan when we can– nothing goes better with spaghetti bolognese than Irving doing “Blue Danube” as a pasodoble. The finessed piano stylings on Bagels and Bongos are only a taste of what Irving has done over the years– everything from horn-honking sock-hop twists and velvet mash-ups of Beethoven and Tchaikovsky to odes to Davy Crockett and Costa Rica. There’s also this 70s sizzler, “West Indies”, a tight bit of electric, Fender bass funk fom his 44th LP (!) Caribbean Cream, released on the Ford label. The congas come courtesy of one of Latin jazz’s top players, Bobby Matos. The copy of I have was signed by Irving in 1977: “To Mary and Rod, two wonderful people!” Irving has always been all about his public and in 1960 he even tried to teach his fans how to play piano on an E-Z Learn LP. If you follow the eight steps and practice on the piano keys sketched on the LP’s back cover, you’ll be playing “Mary Had A Little Lamb” as a rumba in no time. Give it a try, and let a little Irving in your life.

+img037+copy.jpg)